What the heck are these new moth-looking things and why do they seem unstoppable? Although I may be living in Oklahoma, my family still lives back home on the east coast and recently there has been a lot of chatter over there about the spotted lanternfly invasion. These bugs are one of the many species that have been introduced into the U.S. in the past century and are currently wrecking havoc on east coast trees and plants (including those in my aunt’s garden). But what’s the big deal with invasives? Why can’t something just eat them so we can move on?

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. Although we may be separated by continents and oceans, a lot of the living conditions for plants and animals across the globe are similar. The big difference is that the plants and animals living in a certain area, have evolved with each other over time, keeping a system of checks and balances within their own systems.

Take the spotted lanternfly for example, in their origin range in China, there are tiny wasps that lay eggs inside of baby lanternflies, which kill them. This keeps the lanternfly population from getting out of hand. However, in the U.S., living conditions for the lanternfly are similar (e.g. similar temperature, seasons, rainfall, etc.) but the wasps are missing, allowing the lanternfly populations to thrive. There are some natural predators of the lanternflies (such as praying mantis and birds), but none that are familiar with or can control the fast growing population of these new insects.

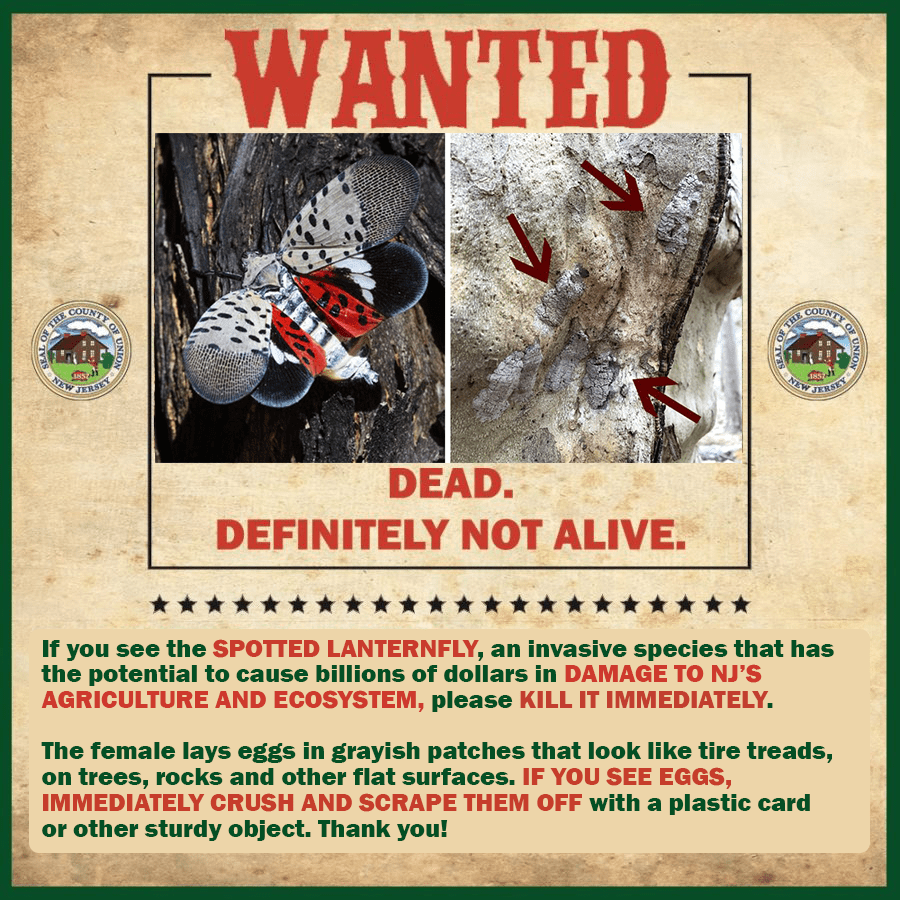

So what do we do? The answer is quite complicated. Typically, in instances of new species introduction, the first thing we try to do is rid of the species as much as possible and hope it doesn’t bounce back. This is why there have been so many PSAs and public science projects encouraging people to kill lanternflies when they see them (because right now we’re their biggest predator).

However, that doesn’t always work (as we have seen this past summer). Sometimes we can’t feasibly kill all of the invasive insects or plants, especially if they’re good at hiding (like emerald ash borers that hide inside of tree bark), are fast producing or are tasty to animals (like wineberries, which are eaten and dispersed by many animals).

However, we can try our best to control the population size with the tools we have at hand. For plants specifically, there have been campaigns surrounding the “eat your invasives” idea, which encourages people to remove and eat invasive plants, as they can be quite delicious (e.g. wineberry and garlic mustard in the Northeast). This idea helps reduce the population size of the plants and inhibits their ability to produce more seeds.

Now obviously the same ideas don’t apply for insects, we can’t all go running around frying up some spotted lanternflies or emerald ash borers (I mean maybe you can but really how many of us are eating bugs on purpose?). This is why the ‘killing on site’ idea for spotted lanternflies came about.

Maybe we can’t rid of them all, but we can do our best to lower their population numbers enough so that they cause minimal amounts of damage to our trees and plants. For something like the emerald ash borer, which specifically targets ash trees, some parks and properties have resorted to removing their ash trees as a pre-emptive plan to stop ash borers and reduce damage caused by dying ash trees.

Some recommendations have been made to introduce the natural enemy of the invaders into their new area to help mitigate population growth, but this comes with its own precautions. We’re talking about fighting a new species with another new species. What happens if the new predator kills off all of the intruders? Will it move on and cause more damage than the intruder? Or will it peacefully coexist in its new are? We just don’t know, and sometimes the risk is not worth taking.

When it comes down to it, dealing with the introduction of a new species is a complicated process. It takes a lot of planning and research to try and figure out how to solve the problem and even then it can sometimes be impossible. The truth of it all is, nature is unpredictable and when humans accidentally (or purposefully) mess with it, the consequences are unknown until they happen, leaving us on a slippery slope of trying to solve them.

At the end of the day, we try our best to deal with the invasive species, but chances are they’re probably not going away— we just have to try our best to limit their growth.

So what can you do about it? This one might be obvious, but don’t bring strange bugs or plants back from different areas outside of your home range (although most flying laws prohibit it anyways). Read up on the invasive species in your area and research ways that you can help combat the population spread. It may be as simple as stomping on a spotted lanternfly when you see it or pulling up a plant out of the ground and throwing it out (or eating it– if it’s safe). Stay informed with your local wildlife organizations and government on how you can do your part. As always, do your best to be kind to the world around you.

Want to support my work? Buy me a coffee!

Want to be notified when new posts are out? Sign up for email notifications below!

Leave a comment